It may seem alluring to view Jack Robinson’s achievement of winning an Olympic surfing silver medal as the culmination of a preordained fate for Australia’s second medal in the sport since its recent addition at the previous Games. However, this narrative is significantly more intricate and remarkable than a mere destiny.

At just 26 years old, Robinson has been riding the waves of Western Australia since he could take his first steps. By the time he reached his teenage years, he had already secured a major sponsorship deal and earned the title of “the next Kelly Slater.” As a young surfer, he was recognized as one of the world’s best barrel riders prior to even reaching adulthood. The prospect of clinching a World Surf League title appeared inevitable, as Robinson inherited a storied Australian legacy in global surfing, following in the footsteps of legends like Mick Fanning and Joel Parkinson.

Nevertheless, the paths of athletes are rarely straightforward. While Robinson’s silver medal at Teahupo’o – an honor only second to local standout Kauli Vaast in the finals – could be seen as the logical progression of his surfing prowess, it was a triumph that felt distant when he stepped away from competitive surfing six years ago.

True talent is not always sufficient to secure gold medals and world championships. Many of the sport’s elite falter under pressure during competitions. After being hailed as a prodigy throughout his youth, Robinson found the competitive landscape to be a challenging adjustment—perhaps an adjustment too daunting to handle.

In 2018, at just 20 years old, he narrowly missed qualifying for the WSL, the pinnacle of competitive surfing. The qualifying series, which is the second tier of competition, demands fierce battles in unpredictable conditions across various locations worldwide—a grueling endeavor involving relentless travel and inferior wave conditions.

For a surfer raised in the midst of some of the globe’s best surfing spots, this was an unwelcome surprise. “My perspective wasn’t particularly positive – especially when the waves weren’t good,” Robinson recalled. Complications also arose from family dynamics, as he was traveling alongside his father, who acted as his coach, commercial manager, and confidant.

Thus, Robinson decided to take a hiatus from the sport. Many elite surfers have stepped back from competitive events, opting instead to make a living through free surfing and sponsorships. For a moment, the next big thing—the surfer who admired three-time world champion Andy Irons—was on the brink of choosing a very different trajectory.

Suddenly, things began to fall into alignment, partially thanks to his now-wife, Julia Muniz, who he credits with helping shift his mindset. In 2019, Robinson qualified for the WSL. In his first four years on the tour, he has already clinched seven event victories and is currently ranked third in the world, with one event remaining before the finals. It appears to be only a matter of time before he claims a world title.

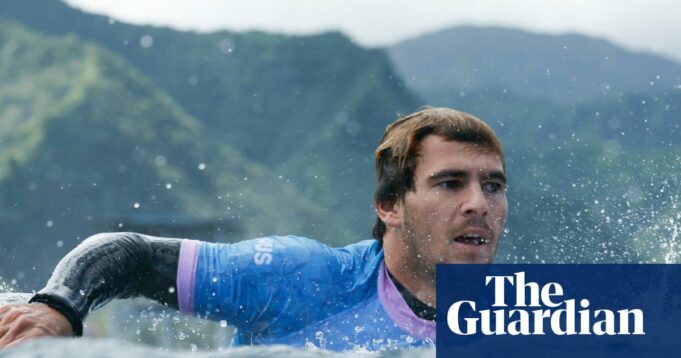

Robinson in action at Teahupo’o. Photograph: Fazry Ismail/EPA

Reflecting on his childhood memories, Robinson thought back to those moments while competing for an Olympic medal on Monday. “I remember when I was young, how much I admired Andy [Irons],” he said afterward. “I envisioned myself doing this for that kid who felt inspired or motivated to be here one day on this stage. Those memories just come rushing back.”

If there is any hint of disappointment in Robinson’s silver medal (coming three years after Owen Wright secured bronze for Australia in Tokyo), it stems from the less than favorable conditions. Following some significant swells earlier in the Olympic window, Monday’s finals were held under the less-than-ideal waves that Teahupo’o is famous for. Vaast, the local star, is an undoubtedly deserving champion—his wave knowledge is unmatched. However, a showdown in substantial barrels between Vaast and Robinson would have provided a much more fitting climax to an event that has done much to affirm surfing’s rightful place in the Olympic framework.

Despite this, securing silver is an outstanding accomplishment for Robinson—one that seemed unlikely when he didn’t qualify for the WSL in 2018. Speaking to Guardian Australia two years prior, while reflecting on his challenging spell away from surfing, Robinson acknowledged feeling the burden of expectations—the pressure to “prove yourself.” He admitted that the stress had affected him: “You can get caught up in that,” he stated. Still, he never doubted his own abilities. “Ultimately, I know I have what it takes. I’ve got the talent and the full package; it’s just a matter of putting it all together.”

In Tahiti, and in recent performances on the WSL, Robinson has successfully done just that. An Olympic medal serves as a well-deserved reward for a journey filled with more twists and turns than initially perceived when he was first labeled as the next generational talent in surfing. Robinson has now matured, and it wouldn’t be surprising to see him earn more medals and capture his first WSL title in the coming years.

However, the difficult years on the qualification tour and his break from competition imparted a valuable lesson that he appears to have fully embraced in recent times. “It’s easy to get ahead of yourself—you want to win everything,” he noted. “It’s also important to enjoy the ride.”