Noah Lyles proved his critics wrong with an extraordinary performance in the men’s 100m final in Paris on Sunday night.

The outspoken American seemed to struggle in the preliminary rounds, finishing behind Team GB’s young talent Louie Hinchliffe and Jamaica’s Oblique Seville.

Meanwhile, Lyles’ compatriot Kishane Thompson appeared to be in top form. However, Lyles, who secured the world championship title in Budapest last year, delivered his finest run when it counted the most.

He has etched his name among the legends of American sprinting, achieving the fastest 100m final ever and claiming the first gold in his quest for a Paris hat-trick.

The newly crowned Olympic champion shared insights with Mail Sport’s DAVID COVERDALE last month about his struggles with depression and how he regained his confidence leading up to the Games.

Noah Lyles was crowned as the new men’s 100m Olympic champion after an epic race on Sunday night

The 27-year-old finished just 0.005 seconds ahead of Jamaica’s Kishane Thompson (yellow jersey)

In 2022, he defended his 200m world title in Oregon and celebrated by ripping his US vest

You likely know him as the confident, vest-ripping, gold medal-winning sprint star. The American with ‘main character energy’ stars in a new Netflix series and is anticipated to be a leading figure at the Olympics.

Yet, there’s another side to Noah Lyles, a vulnerability that lies behind his brash exterior. His previous Olympic appearance was overshadowed by personal struggles.

‘I was battling depression,’ Lyles revealed about his experience at Tokyo 2020. ‘I was coming off my antidepressant medication because I was experiencing significant weight gain. There was a lot happening at that time.

‘It felt like I was just trying to put on a brave face. When I reviewed my Tokyo race, I thought, “I don’t recognize that person. That’s not the Noah I know.”

‘It was unsettling at times; I questioned why I acted the way I did. Each day, I wake up thankful that I’m not in that situation anymore.’

Lyles’ struggles didn’t begin with Tokyo. He has been in and out of therapy since childhood, having faced bullying in school due to his yellow teeth, a condition caused by ADHD medication, alongside dealing with asthma and dyslexia.

His mental health really took a hit in 2020 due to a combination of the pandemic, the uncertainties surrounding the Olympics, and the fallout from George Floyd’s death. When the Tokyo Games finally took place behind closed doors in 2021, Lyles could only manage a bronze medal in the 200m, despite being the reigning world champion in 2019.

He didn’t even qualify for the 100m event.

American sprint sensation Noah Lyles has admitted he suffered from depression

There is another side to Lyles, a vulnerability hidden beneath the showman’s bravado

Fast forward three years, and Lyles has claimed the titles for both 100m and 200m, and is thriving both on and off the track. What’s behind his newfound happiness? ‘A lot of therapy,’ the 26-year-old shares with Mail Sport. ‘I have two therapists: one who focuses on sports and another who helps with personal life issues.

‘There’s a lingering fear that depression might return. But each time that thought arises, I remind myself how much I’ve improved and how great I’m doing. I see it as the negative voice trying to pull me back.’

While that voice had a grip on Lyles three years back, he views the pain from his time in Tokyo as a catalyst for his recent successes. In 2022, he defended his 200m world title in Eugene, celebrating in iconic fashion by ripping open his US vest.

Just a year later, in Budapest, he became the first man since Usain Bolt to achieve a treble in the 100m, 200m, and 4x100m relay at the World Championships.

‘That bronze still ignites a fire in me,’ admits Lyles, who set a personal best of 9.81 seconds to win the 100m at the London Diamond League. ‘I’ll carry that memory to Paris as a reminder that I’m not returning with anything but gold.’

‘I’ve always been candid about my disappointment surrounding 2021 and how it fueled my drive. It was pivotal in shaping my achievements since then.

‘I believe that if I had won that gold medal, I might have become complacent, hindering my growth these past two years.’

Lyles has evolved not only as an athlete but also as a public figure. Alongside his leading role in the Netflix documentary *Sprint*, which features some of the fastest runners globally, he’s made guest appearances on *The Tonight Show* and graced the cover of *Time* magazine this year.

Lyles revealed the bronze medal he won in the 200m at the Tokyo Olympics still pains him

He has grown both as a sprinter and as a celebrity and now just needs to win Olympic gold

While Lyles prefers not to be compared to Bolt, he undoubtedly possesses a unique star quality that could elevate him beyond the sport since the Jamaican’s retirement in 2017. A gold medal at the Olympics would propel his fame and solidify his status as an icon, a concept reflected in a tattoo on his body.

‘I’m surprised by the level of attention the Netflix show has garnered,’ Lyles shares. ‘I run past high school students who scream, “Hey, that’s Noah Lyles, can I grab a picture?” Groups of them stop me! I’m not sure I can venture out solo anymore!

‘Succeeding in the Olympics would raise the stakes, allowing me to advocate for even more opportunities.’

Because of his significant role in *Sprint*, he collaborates closely with Box to Box producers—famous for *Formula 1: Drive to Survive*—to enhance his storylines for the ongoing second season. However, Lyles’ vision extends beyond his own fame; he aims to uplift athletics as a whole.

‘We’re focusing on creating engaging narratives so viewers will be eager for each upcoming track meet,’ Lyles reveals. ‘We want to entertain and create opportunities for more athletes to gain recognition.’

‘I’m driven by my aspirations and joy, yet it aligns with a broader goal: seeing track and field flourish and improve by the time I leave.’

When Mail Sport first spoke to Lyles last December, he laid out plans to enhance the sport’s visibility, suggesting the introduction of four major annual events globally, similar to tennis. This vision has begun to materialize after American legend Michael Johnson launched Grand Slam Track, a series of four yearly meets with $100,000 (£77,000) prizes for the athletes.

Lyles is not only interested in boosting his own popularity but athletics as a whole

American hurdler Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone and British middle-distance star Josh Kerr are the first athletes to join the lucrative series. Will Lyles be next?

‘I can’t confirm if I will be part of it yet,’ he responds. ‘Discussions are ongoing, but I’m thrilled to see positive developments. The last thing I want is inaction.’

‘There’s a collective desire for change and enthusiasm for fresh opportunities in track. I hope it brings great benefits for everyone involved.’

Lyles has long advocated for better rewards for athletes, supporting World Athletics’ controversial move to offer $50,000 (£38,600) to Olympic gold medallists.

‘I’m proud of World Athletics for stepping up; it’s something that should be handled by the IOC (International Olympic Committee),’ he reflects. ‘I received many messages after the announcement, questioning if we weren’t already compensated. Others asserted that a gold medal should hold more value, and that’s a discussion worth having.’

Another critical issue is doping within athletics, a long-standing concern for the sport. At the last Olympics, Great Britain lost their 4x100m relay silver medal after CJ Ujah tested positive for banned substances and received a 22-month ban.

The unexpected 100m winner in Tokyo, Marcell Jacobs, also faced scrutiny after his past nutritionist became connected to a steroid distribution investigation. Jacobs was ultimately cleared in court and never accused of misconduct.

Does Lyles believe all his competitors are clean? ‘I can’t provide proof; it’s not my responsibility,’ he states. ‘Of course, I may have suspicions, but if you’re on that starting line, I assume you’re clean, and it’s my job to outperform you. Even if you’re not, I trust my abilities enough to surpass you.’

He is eyeing up shattering records in Paris and believes he is in the best shape of his life

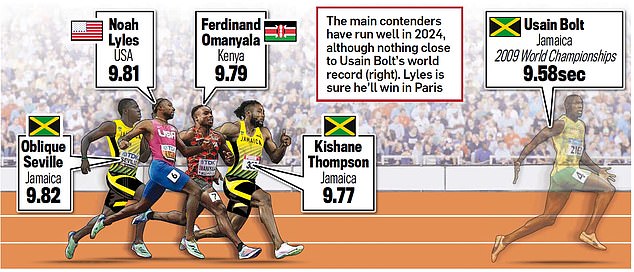

Lyles’ time at the London Stadium was only the third-fastest in the world this year. Kishane Thompson recorded the fastest time globally in 2024 with 9.77 seconds at the Jamaican trials, while Kenya’s Ferdinand Omanyala clocked in at 9.79 seconds.

However, Lyles is confident he’ll be the fastest at the Stade de France this summer. He’s targeting Tyson Gay’s American record of 9.69 seconds in the 100m, which he dubs his ‘mistress’, as well as Bolt’s world record of 19.19 seconds in the 200m, the race he refers to as his ‘wife.’

‘I am in the best shape of my life,’ he asserts. ‘I’m achieving training times that are new for me. The American record is constantly on my radar in the 100m, and in the 200m, I aim to hit 19.10 seconds.’

‘In the indoor season, I improved my 60m time by 1.02 percent. If I apply that to the 100m, I should be breaking records. And if I factor that into my 200m performance, I should manage 19.10.’

For Lyles, though, accumulating medals remains the priority. As early as December, he expressed a desire to include the 4x400m relay in his Olympic program to secure four golds—an achievement even Bolt never realized. Yet, after he ran a 4x400m leg at the World Indoors in Glasgow in March, it stirred debates in the US, with other athletes and coaches accusing him of ‘favoritism.’

This controversy has cast doubt on his aspirations, but Lyles insists: ‘Anyone on the US team can be part of the relay pool. It’s up to the relay coaches to decide. If they want me, I’m ready. I won’t take offense at their choices.’

After Japan’s empty stadiums, Lyles is relishing the prospect of performing in front of a crowd

Regardless of whether the quadruple remains achievable, the treble is certainly within reach. Following the vacant stands in Japan, Lyles eagerly anticipates competing before a packed audience in France.

‘As a performer, I thrive on the energy of an audience and the pressure it brings,’ he notes. ‘The more attention on me, the better I compete. The moment the lights are on and the viewers are watching, losing isn’t an option. I live for those high-stakes situations.

‘Arriving in Tokyo to an empty stadium, where my footsteps echoed, was surreal. But Paris will be a completely different experience. Everything will be amplified to a thrilling level.

‘The Olympics is the ultimate stage, and currently, I am without an Olympic gold medal. However, following Budapest, it feels like, “We’ve done this before, and now we’re ready to do it again”.