Creative justifications in doping cases have a long history, with one standout example being Dennis Mitchell, a former Olympic sprint medallist for the United States, now in Paris coaching Sha’Carri Richardson.

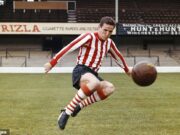

Looking back to 1988, Mitchell faced serious repercussions when he was caught with elevated testosterone levels in his sample. His excuse became legendary, claiming it resulted from having ‘at least’ four sexual encounters with his wife in one night, stating, ‘It was her birthday, the lady deserved a treat.’

Unfortunately for him, that excuse didn’t hold water – he received a two-year ban, and more than thirty years later, it still pops up in discussions and jokes.

It’s often easier to laugh when the issue arises elsewhere. As the four-year Olympic cycle progresses, there’s a common tendency to assume the worst about foreign athletes, especially when their explanations seem dubious. Conversely, there tends to be more leniency when British athletes are involved in doping scandals.

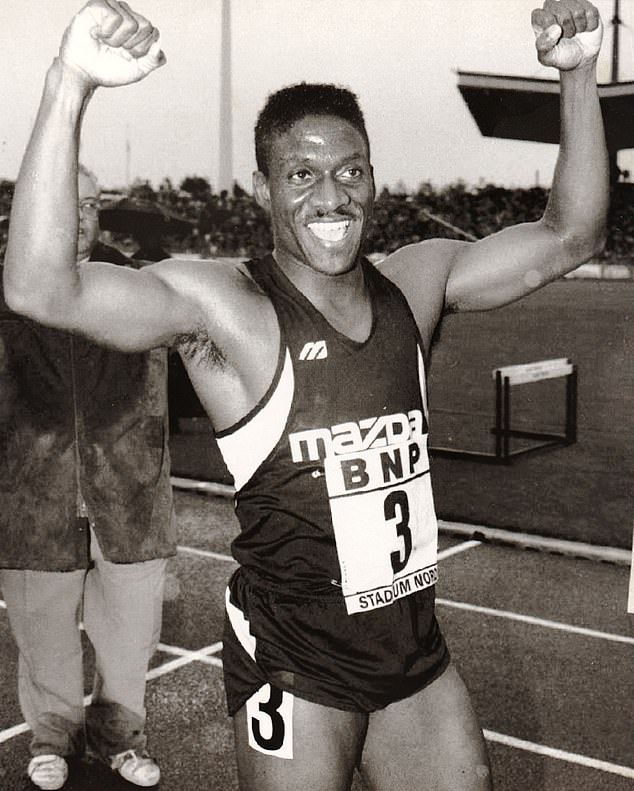

This has been a notable month for such cases. You may have heard about the Chinese swimmers, particularly the 11 in France, who were part of a group of 23 that tested positive for a banned substance before the Tokyo 2021 Games.

I feel awkward about the less publicised case closer to home around Jade Jones, a two-time Olympic taekwondo champion going for a hat-trick in Paris, writes Riath Al-Samarrai

If we go back to 1988, Dennis Mitchell found himself in a spot of bother after being busted for high levels of testosterone in his sample

The Chinese swimmers? You will likely know about them by now, and more precisely the 11 here in France (including Qin Haiyang, pictured) who were among a group of 23 who failed tests for a banned substance ahead of the Tokyo Games of 2021

They were ultimately cleared because the authorities acknowledged they were likely victims of contamination from the same hotel kitchen, even though there are now doubts regarding whether all of them stayed there. The nature of the investigation and the claims of a significant cover-up have left many feeling very uneasy.

Simultaneously, I feel uncomfortable about the lesser-known case involving Jade Jones, a two-time Olympic taekwondo champion, who is pursuing a third gold in Paris.

Her case, which emerged just two weeks ago, is unlike any I’ve encountered in relation to doping. She faced a violation for refusing to take a drug test last December but avoided a four-year ban due to being deemed to have experienced ‘loss of cognitive capacity.’ Shockingly, she received no sanction at all for such a serious infraction, as UK Anti-Doping determined she was ‘without fault or negligence.’

The UKAD report, spanning eight pages, is full of intriguing details, and it’s tempting to reflect on how this situation could be perceived internationally. How would we respond if the roles were switched?

This event traces back to 6:50 am on December 1 at the Leonardo Hotel in Manchester, where Jones was residing. As familiar to elite athletes in this country, and particularly an experienced competitor like her, a drug tester arrived. Having been part of the Olympic program for her entire adult life, she understood the process – it’s drummed into them through training sessions and literature about the serious implications of any mistakes. Yet, Jones chose not to take the test.

She articulated her reasons, which could spark an interesting discussion regarding athlete welfare – she informed the female collection officer that she was in the process of cutting weight for a weigh-in scheduled for 10 am that same morning and had not eaten or drunk anything since November 29. As a result, she felt unable to provide a urine sample and was about to head home for a dehydration bath.

What’s concerning is that she did not permit the officer to accompany her, despite the officer’s willingness to assist and monitor her until she was ready. By the time Jones departed the hotel at 7:43 am, she had been reminded ‘approximately five times’ about the consequences of refusing the test, in addition to having received advice to comply during a phone conversation with GB Taekwondo’s performance director, Gary Hall.

Legal matters unfolded over the coming months. In February, there was a meeting involving UKAD, Jones, and her lawyer, where she expressed that she had been ‘stressed and panicked’ that morning due to her weight situation. She also mistook the severe repercussions of refusing the test for those associated with the three-strike rule for missed tests. Again, it’s striking that she is a seasoned Olympic competitor.

We should state here that there is no suggestion Jones committed any wrongdoing beyond the violation of refusing a test. But it is a remarkable situation for such an experienced athlete

The Chinese swimmers (including Zhang Yufei, left, and Wang Shun, right, who claimed gold in Tokyo) were cleared, because the authorities accepted they fell foul of contamination from the same hotel kitchen

Seven weeks after that meeting, Jones had a different legal representation along with a new argument. They introduced a medical condition, which has been redacted in the UKAD report, that a consultant psychiatrist indicated could ‘fully explain the situation’. This assessment was deemed ‘compelling’ by a psychiatrist appointed by UKAD.

Fast forward to today, and Team GB is unwavering in their support for Jones’s participation. As mentioned by their esteemed chef de mission, Mark England, Jones did complete a drug test later that same day, December 1, and was consequently cleared.

However, he misspoke regarding the timeframe. He casually suggested it occurred ‘a couple of hours later,’ while according to the UKAD report, it was actually at 7:20 pm, nearly 12 hours later. In discussions about doping and substance clearance, timing is crucial.

It should be emphasized that there is no implication of wrongdoing on Jones’s part beyond her refusal to take a test. Yet, it presents a remarkable situation for such an adept athlete.

It raises a thought-provoking question, particularly about how public perception may differ if this involved one of Jones’s competitors. It would be fascinating to learn the views of the Chinese delegation, including their fighter Luo Zongshi, the 2022 world champion in the same weight class as Jones.

They might view it as perfectly acceptable. Alternatively, they could align with Renee-Anne Shirley, a former director from Jamaica’s anti-doping agency and a prominent whistleblower, who recently stated that it ‘smacks of preferential treatment.’

Shirley elaborated, saying, ‘It appears from the outside that this is your gold medallist who has refused to take a test and has evaded any repercussions. After this, anyone may claim, “I’m struggling with a mental health issue” and skip a test.’

Regardless of the correctness of her perspective, it presents a valid point for consideration as we enter another Olympic cycle, where self-reflection is often neglected.

Friday evening’s four-hour parade of interpretive dancing, aspirational messaging and floating staircases only fortified an instinct that there must be a better way

Starting with sending it to the bottom of the Seine and cracking on with the hop, skip and jump

Personally, my greatest hope is that Katarina Johnson-Thompson finally gets her medal

Must be a better way than Friday’s four-hour parade

A few thoughts on Olympic opening ceremonies: while a certain cost is expected to access what is undoubtedly the greatest sporting spectacle, the four-hour parade of interpretive dancing, aspirational messaging, and floating staircases only reinforced the feeling that there must be a more effective way. A starting point could be to toss it into the Seine and get on with the activities.

My greatest hope this Olympics

Rumor has it that Team GB anticipates most British medals to come from cycling and rowing, with potential surprises in athletics. Conversely, concerns surround boxing not performing to its usual standards. Personally, I hope that Katarina Johnson-Thompson finally secures her medal, as she truly represents the Olympic spirit of perseverance.